The De Profundis takes its name from the first two words of the psalm in Latin. It is a penitential psalm that is sung as part of vespers (evening prayer) and in commemorations of the dead. It is also a good psalm to express our sorrow as we prepare for the Sacrament of Confession.

Every time you recite the De Profundis, you can receive a partial indulgence (the remission of a portion of punishment for sin).

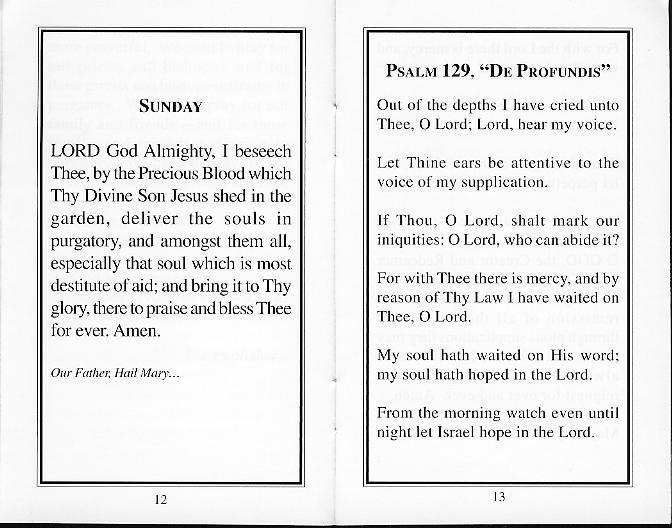

Out of the depths I cry to You, O Lord; Lord, hear my voice. Let Your ears be attentive to my voice in supplication. If You, O Lord, mark iniquities, Lord, who can stand? But with You is forgiveness, that You may be revered.I trust in the Lord; my soul trusts in His word. My soul waits for the Lord more than sentinels wait for the dawn. More than sentinels wait for the dawn, let Israel wait for the Lord. For with the Lord is kindness and with Him is plenteous redemption; And He will redeem Israel from all their iniquities.

From the source:

Psalm 130

1 Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord.

2 Lord, hear my voice!

Let your ears be attentive

to the voice of my supplications!

3 If you, O Lord, should mark iniquities,

Lord, who could stand?

4 But there is forgiveness with you,

so that you may be revered.

5 I wait for the Lord, my soul waits,

and in his word I hope;

6 my soul waits for the Lord

more than those who watch for the morning,

more than those who watch for the morning.

7 O Israel, hope in the Lord!

For with the Lord there is steadfast love,

and with him is great power to redeem.

8 It is he who will redeem Israel

from all its iniquities.

Mary of Egypt left a life of sin and lived a life of repentance. Here is synopsis of her life from a book I recently read, The Cloister Walk by Kathleen Norris

Mary of Egypt lived in the fifth century, but her story is all too familiar in the twentieth. Running away from home at the age of twelve, she became a prostitute in Alexandria. At the age of twenty-nine, she grew curious about Jerusalem and joined a boatload of pilgrims by offering the crew her sexual services for the duration of the journey. She continued to work as a prostitute in Jerusalem. On hearing that a relic of the true cross was to be displayed at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, her curiosity was aroused again, and she joined the feast-day crowds. But at the threshold of the church some invisible force held her back. Suddenly ashamed of the life she’d led, she began to weep. Kneeling before an icon of the Virgin Mary, she begged forgiveness and asked for help. A voice said to her, “If you cross over the Jordan, you will find rest.” Mary spent the rest of her life, forty-seven years, as a hermit in the desert. Late in her life, Mary encounters a monk who had come to the desert for a period of fasting, and she tells him her story. . . . The monk is amazed to discover that Mary knows many Bible verses by heart, for in the desert she has had no one but God to teach her. She asks him to bring communion to her, when next he comes to the desert, and this he does. On his third visit, however, he finds that Mary has died. . . .

Monks have always told the story of Mary of Egypt to remind themselves not to grow complacent in their monastic observances, mistaking them for the salvation that comes from God alone. And in the Eastern Orthodox churches, Mary’s life is read on the Fifth Sunday of Lent, presented, as the scholar Benedicta Ward tells us, “as an icon in words of the theological truths about repentance.” . . . . Repentance is not a popular word these days, but I believe that any of us recognize it when it strikes us in the gut. Repentance is coming to our senses, seeing, suddenly, what we’ve done that we might not have done, or recognizing, as Oscar Wilde says in his great religious meditation De Profundis, that the problem is not in what we do but in what we become. Repentance is valuable because it opens in us the idea of change. I’ve known several young women who’ve worked in the sex trade, and one of the worst problems they encounter is the sense that change isn’t possible. They’re in a business that will discard them as useless once they’re past thirty, but they come to feel that this work is all they can do. Many, in fact, do not like what they become.

The story of Mary of Egypt opens the floodgates of change. . . . The monk who encounters Mary still has a lot to learn; his understanding of the spiritual life is facile in comparison to hers, and he knows it. Mary, for all her trials, is like one of those fortunate souls in the gospels to whom Jesus says , “Your faith has made you whole.” Benedicta Ward has said that these stories are about deliverance from “despair of the soul, from the risk of the tragedy of refusing life, of calling death life,” which may be one function of the slang term for prostitution: it is called “the life.” But the story of Mary of Egypt is one any of us might turn to when we’re frozen up inside, when we’re in need of remorse, in need of the tears that will melt what Ward terms “the ultimate block within [us]; that deep and cold conviction that [we] cannot love or be loved.” In this tradition, Ward says, virginity, defined as being whole, at one in oneself, and with God, can be restored by tears.

from Norris, Kathleen (1997-04-01). The Cloister Walk (pp. 164-166). Penguin Group US. Kindle Edition.

No comments:

Post a Comment